Bigger and Bigger and Always Black

I’m married to a BIG black man.

I’m married to a BIG black man.

Some might say he is larger than life.

His ear-to-ear smile brightens every room. His BIG laugh is hilarious and makes others break into chuckles even if they didn’t hear the joke.

His BIG shoulders (although very annoying on an airplane) have held many, many heads. And his BIG bear hugs are second to none.

But not everyone is endeared to bigness or blackness.

We’ve seen the very traits I love in my husband become the subject of black mortality—when police and other figures of authority preside, and when “average Joes” become overcome with fear and hate they might not even be aware of.

When we met in college at our tiny liberal arts school, my then boyfriend was a “big man on campus.” Certainly he was known to most.

Since college, he has gotten bigger and bigger—professionally and financially, and maybe physically, too—just a little bit.

Despite his big, engaging, extroverted personality, he is an understated guy, particularly in how he dresses and presents himself.

I returned the “black jeans,” as my husband—who is from Ghana—referred to them. They fit an American stereotype of black fashion with extra bling and embroidery on the pockets. The jeans weren’t his style, but they were the only ones that fit his backside.

My big black man works in Silicon Valley and has been fortunate to find a work culture that allows hoodies and jeans as part of the dress code, though I’m not sure any dress code exists.

He drives a black Camry because he doesn’t want to draw attention. He is BIG in so many ways, but also restrained. The understated parts are a conscious choice—the small but insidious adjustments made by people of color in an attempt to make themselves look smaller and less “offensive”—and therefore less likely to incite fear and hate.

My husband learned to wear a T-shirt and jeans in Portland, OR. Our employee discount at the Nike store helped, and athletic apparel was both socially accepted and expected at his job.

He later carried those ideas back to his childhood home in Ghana—a place where big men often wear 3-piece suits in 100-degree heat. Not at his office.

He led by example and expected that the work—their product—speak for itself. Wear whatever you want, but the work was the priority, not trappings of seniority or power.

We returned to the US, and damn that hoodie took on new meaning.

He ditched the hoodie and opted for the button-down shirt—the norm in his New York City office.

My big black man is a chameleon and he will adapt as necessary in order to be successful, but also to stay alive—to try to appear as though his bigness and blackness is not a threat; not something to cause a reasonable person to “fear for their life.”

He is currently in Cannes, France at the advertising awards—baller, I know.

I laughed out loud when he told me he was moderating a Facebook panel on fashion with the CEO of Gucci, Marco Bizzarri. I think he is most proud to participate in a panel discussion on diversity in the ad industry (which is sorely lacking)—moderated by Maverick Carter, LeBron’s manager, and introduced by Jack Dorsey.

As I write this, he just sent a photo of himself at dinner…on a yacht…sitting next to Halle Berry.

Yep, my husband is a successful black man, hobnobbing with the rich and famous, and maybe even he has a seat at the table.

But none of that matters. Not his smile, not what he wears, not his education, his money, status or success.

Well, the money helps. Poor and black is a whole other category of hurt.

We live in a small, coastal community: an obscure little town separated from the Silicon Valley hubbub by a little mountain and a single-lane highway connecting the beach and farms to the rest of the bay.

He left early one morning for work, stopped to get gas, and in his distracted state of the morning rush, he backed into someone’s car.

The fender bender was completely his fault and he said so.

He decided to flag down a nearby cop, and then instantly regretted it. He wanted to do things right—“by the book,” and was suddenly completely overcome by fear that he might get arrested, beaten, or killed by the police simply for being black.

It all ended well and without incident. But he drove to work with white knuckles and couldn’t get his stomachache to go away for the rest of the day.

My beautiful big black man was wracked with fear in hindsight—over what could have happened.

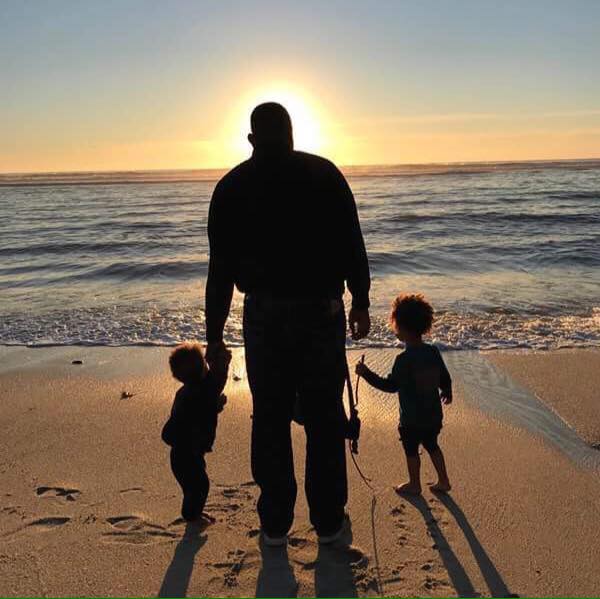

For the offense of making a mistake and then being a good samaritan, his sons could have lost their father. I could have lost the love of my life.

I drive when our family is in the car together. I get motion sick; I’m a control freak.

And I want my whiteness to protect my husband and our two little boys.

Because even driving a minivan, you never know what can happen.

I worry a lot for my husband and our two sons. I wish, hope and pray every day that my whiteness can protect them. That our money and status and choice of community—our privilege—will protect them.

Sometimes I wish my big black man wouldn’t wear a hoodie—or at least that he wouldn’t put the hood up. And then I hate that I wish that because I want him to feel free. Living with fear about my husband is exhausting.

I’m proud of our son’s big, beautiful, curly hair. But it draws attention.

I hate that it’s political—he’s only 3. Lots of days I want to cut it. And then I hate when I have that wish, because I want my son to feel free to wear his beautiful hair the way he chooses. Living with fear over my children is exhausting.

My boys are obsessed with vehicles, especially the ones with sirens. But my skin bristled reading a bedtime book that showed the police car with the bars—“to keep the police safe” from the bad guys and, oh yeah—the page that introduced the other police vehicle, the paddy wagon, where the bad guys go.

My skin bristled when the cops, who were keeping the cyclists safe during the local triathlon, gave stickers to my kids. I hated my reaction and I desperately wanted to feel “normal.” Fear and worry and doubt is exhausting.

Damn I was missing my privilege in that moment.

July 6th will be one year since Philando Castile was shot to death by a police officer.

I couldn’t watch the Facebook live video captured by Castile’s girlfriend, and I haven’t watched the just-released dash cam video. But a year ago, I read the news stories and I thought, this time will be different. Castile’s family will get justice.

The cop was suspended and then, after protest, fired. I thought, with this video, with all of the “facts” about the incident that were being reported, there was no way this cop would be acquitted.

I told my husband, “If Yanez is acquitted, I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

He told me, “We’ll see.”

Macalester College English Professor, and winner of the 2015 Man Booker Prize for Fiction, Marlon James, wrote an essay last week titled, “Smaller and smaller and smaller.” The essay is a searing criticism of racism in Minnesota and one that speaks to me deeply, in part, because that’s where I’m from.

James perfectly describes our different reactions to the acquittal of Castile’s murderer:

“…brewing fresh outrage every morning is not a privilege people of colour get to have. The situations that cause outrage never go away for us. It never stuns us, never comes out of the blue. We don’t get to be appalled because only people expecting better get appalled.”

I worry my husband is becoming numb. He’s not outraged anymore.

Yes, I think at one point he was. He is an African who assimilated to be a black man in America, but that is perhaps an essay for another day.

Behind his big, big smile, I know he is angry. Angry in a way none of his colleagues—and most people in his life will never see.

He buries it. He channels it. He is a pragmatist. He “doesn’t have time for useless emotions,” like my mom-guilt or worry or outrage. He doesn’t have time for his own anger. He just gets on with it.

He is a BIG black man. And despite his understated appearance and attempts to blend in and not draw attention, my husband is a big man in every sense of the word.

All of his bigness brings me pride, and feelings of comfort and safety—and so much joy.

My husband will never be smaller even if he tries. And as James says, “reduction” is futile, “…because I’m never the one with the measuring stick.”

I am appalled, full of rage, and weeping and depressed but getting on with being a mom.

And still, I DO expect better. I want this world to be better.

For my husband. For my boys. For our community.

I want them to live and be bigger, and bigger, and bigger.

Without shame. Without fear. Without regret.

“Smaller, and Smaller, and Smaller.” Facebook post by Marlon James. https://www.facebook.com/notes/marlon-james/smaller-and-smaller-and-smaller/10154481835792077/ . Accessed 6/29/2017.